Attached Shadow

An attached shadow is a shadow that appears on the object itself. It is “attached” to the thing casting it. This shadow exists on the part of the object that is turned away from the light source. Attached shadows are fundamental to lighting. They are the primary tool that reveals an object’s shape, form, and texture. And they are what make a two-dimensional image appear three-dimensional.

Attached Shadow vs. Cast Shadow

Filmmakers must distinguish an attached shadow from a cast shadow. The difference is simple.

An attached shadow is on the object. (Example: The shadow on the side of a person’s face, away from the key light).

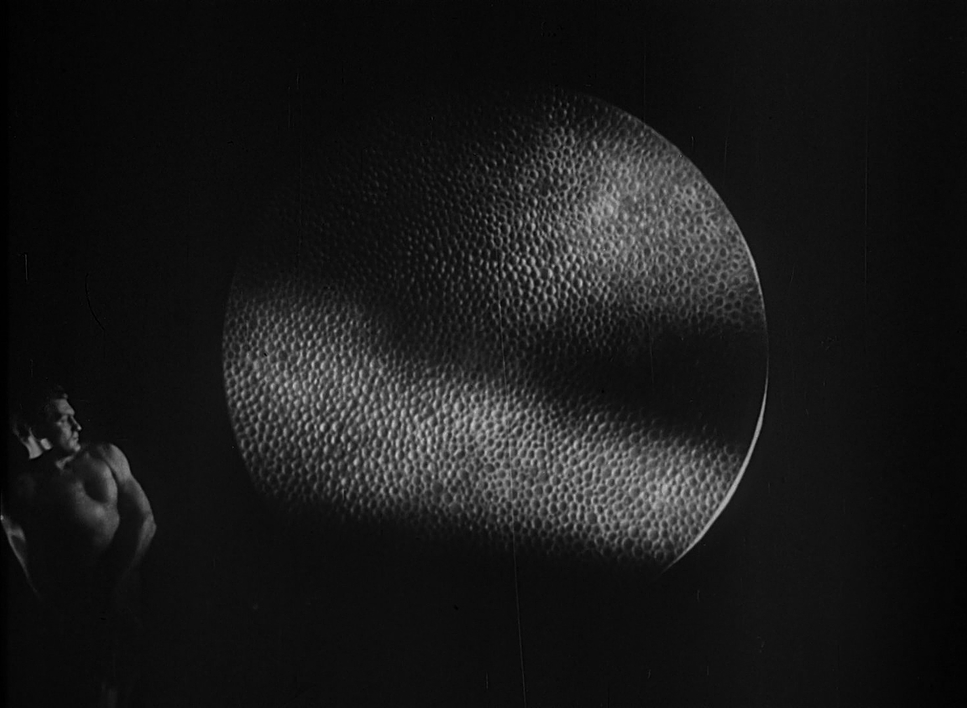

The Big Combo | Timeless Classic Movies

A cast shadow is the shadow the object projects onto another surface. (Example: The person’s shadow on the wall behind them).

Sin City | Miramax

Understanding this difference is key to mastering lighting. Cinematographers actively shape and control both types of shadows.

How They Create Dimension

Attached shadows are the key to creating “modeling” and form. A flat, front-lit object looks two-dimensional. For example, a sphere lit directly from the front looks like a simple, flat circle.

Now, move the light to the side. The sphere instantly gets a bright side (the highlight) and a dark side. That dark side is the attached shadow. This shadow describes the object’s roundness. It convinces our brains that the 2D image has depth. This same principle applies to lighting a human face. These kinds of shadows define the contours of the cheekbones, nose, and jawline.

How Cinematographers Control Attached Shadows

A cinematographer’s main job is controlling shadows. They control these shadows in two primary ways.

- Light Direction: The position of the key light is crucial. A light placed directly in front of the subject creates very few attached shadows. This results in a flat, high-key look. A sidelight, however, creates the most dramatic and defined shadows. This is a common technique to create mystery or drama.

- Light Quality: The “hardness” or “softness” of the light also matters. A hard light (like the direct sun) creates a defined attached shadow. This shadow has a sharp, clean edge. A soft light (from a large silk or an overcast sky) creates a gradual kind of shadow. This shadow has a soft, feathered edge, often called a “roll-off.”

Attached Shadows and Fill Light

Attached shadows are also the key to a scene’s contrast. The darkness of defines the lighting ratio. A cinematographer uses fill light to manage this. Fill light is a separate, softer light source. Its main job is to “fill in” the dark attached shadows created by the key light.

A lot of fill light makes the shadows brighter. This creates a low-contrast image. This style is common in comedies or beauty lighting. Very little (or no) fill light leaves the attached shadows dark. This creates a high-contrast, dramatic, or “moody” image.

In summary, attached shadows are a primary tool for artistic expression. The size, shape, and darkness of these shadows directly create the film’s mood. They guide the viewer’s eye. Mastering them is a fundamental skill for every filmmaker.

« Back to Glossary Index